I first came across a reference to Eugène Marais in Andries Engelbrecht’s very excellent Computational Intelligence: An Introduction. See the links below for details about this highly unusual character.

The Tragic Genius of Eugène Marais (The author, Conrad Reitz, very kindly shared some of his thoughts with me).

Introduction

by Keith Addison

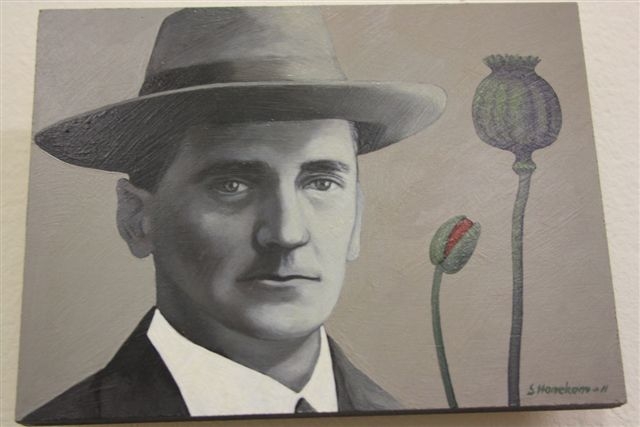

EUGÈNE Marais was a South African poet, a story-teller, a journalist, a lawyer, a psychologist, a natural scientist, a drug-addict, and a great genius — an abused and forgotten genius, and the world is the worse off for that.

He was master of a science that was only invented 50 years later (ethology); it was 60 years before anyone else attempted to study what he’d studied (ape societies in the wild); he described natural mechanisms and systems that were not identified by mainstream science until 40 years later (pheromones); and neither science nor society has yet caught up with many of his findings and conclusions.

As a boy growing up in Cape Town in the 1950s I knew of him as an Afrikaans poet, an early champion of the language of the Boers. We studied his poem Winternag (Winter’s Night) in school, and duly thought nothing of it. He could have taught us so much more, if they’d let him.

Like many of us, I always had animals or birds or creatures of some kind around, or in my pocket or hanging off my clothes — and so did Marais. His son wrote of him: “[He] was never without tame apes, snakes, scorpions, and the like.”

At one time I became fascinated by ants, and spent ages lying on my stomach on the ground studying them. “What are you doing?” my mother asked once. “Counting ants,” I told her. It became a family joke. If only I’d known what Marais had to say about ants!

It was only much later that I really discovered Marais, and I guess most of us still haven’t. Which is rather typical of Marais, and that’s a tragedy — which is also typical of him.

As a scientist it was the mind of man, the human psyche, that preoccupied Marais, and to find the key to its nature it was to nature that he turned, rather than to humans. He followed two parallel paths, the study of the animals most like humans, the primates, and the study of creatures that could hardly be more alien to us, the social insects — termites, known in his day as white ants. In both fields his findings were revolutionary.

In a way Marais was lucky. For entirely unrelated reasons he stumbled upon unique opportunities for his research. One reason for his success was that nobody else had had the chance to do that kind of work before, nor would have again for many years afterwards. But it was what he made of his opportunities that counted. And where Marais’s luck led him was another matter.

Marais was born to a traditional Afrikaner family in the Boer Republic of the Transvaal in 1872. He had a rather strange schooling: the only teacher available was a Church of England missionary who could not or would not speak a word of Marais’s native Afrikaans — known as “kitchen Dutch” in the snooty British colony of the Cape, where it was the patois of the mixed-race Cape Coloured servant-class. So Marais learnt English.

In 1890, at the age of 18, he took his first job, as a journalist for the newspaper Land en Volk (Country and People) in Pretoria, the capital. A year later he was the editor, and by the time he was 20 he owned the newspaper.

His acrid comments as a parliamentary reporter at the Volksraad (People’s Council) saw the entire Council vote to ban him from the press gallery. Later he was charged with high treason for opposing the president, Paul Kruger, but he was acquitted by the Supreme Court.

It was at this early stage of his career that his life-long struggle with drug-addiction began. Marais suffered severely from the acute pain of neuralgia, and someone suggested morphine, which was readily available then. He never shook off the habit. (His son and others referred obliquely to his bouts with the drug as his “ailing health”.)

In 1894 came a severe blow that undoubtedly changed his life. Aged only 22, he married a young woman from Natal, but she died only a year later after their son was born. He never married again. Soon afterwards he gave up journalism, left Pretoria and went to London to study law. He qualified and was admitted to the bar at the Inner Temple. He studied medicine at the same time but in 1899, before he could qualify, the Boer War broke out, and Marais was put on parole as an enemy alien.

The British Redcoats were no match for the fast-moving Boer commandos — 200 years of skirmishes and mutual cattle raiding with the Black tribes had made the tough farmers masters of guerrilla tactics. The British, lacking skill, tried sheer weight of numbers instead — in the end 450,000 of Britain’s cream were pitted against only 80,000 Boer fighters. That didn’t work either.

Britain’s Lord Kitchener finally “solved” the problem. The British cordoned off the land, burned the Boers’ farms and herded their women, children and old people into concentration camps, where more than 20,000 died of disease and malnutrition.

In London, Marais was distraught. He escaped from Britain and was soon in Central Africa heading towards the Limpopo River with supplies of munitions and medicines to aid his countrymen. But before he got there the Boer generals surrendered and the war ended — and Marais caught malaria and landed up in hospital in Delagoa Bay (Mozambique). As with the morphine, he never shook off the malaria, it recurred throughout his life.

The war left him shattered. He wrote later: “The most enduring result was that it made me far more bitter than men who took part in the war at a more advanced age and who had had less to do with the English before the war. It was for purely sentimental reasons that I refused to write in any language but Afrikaans, notwithstanding the fact that I am far more fluent and more at ease in English.”

He did however write several learned papers in English, but for the most part he’d doomed himself and his work to the confines of an obscure language with no influence in the world of affairs, and it was to prove his undoing.

In 1904 Marais returned to Pretoria, but, shunning human society, he soon left for the Waterberg, an isolated range of mountains in the Northern Transvaal, where he and a friend lived for the next three years. This was part of the depopulated farming country Kitchener had cleared, nobody had lived there for years. Marais’s only neighbours were a large troop of wild chacma baboons, which in the meantime had all but forgotten that man is something for a baboon to fear.

Years later he wrote in a letter: “No other worker in the field ever had the opportunities I had of studying primates under perfectly natural conditions. In other countries you are lucky if you catch a glimpse of the same troop twice in a day. I lived among a troop of wild baboons for three years. I followed them on their daily excursions; slept among them; fed them night and morning on mealies; learned to know each one individually; taught them to trust and to love me — and also to hate me so vehemently that my life was several times in danger. So uncertain was their affection that I had always to go armed with a Mauser automatic under the left armpit like the American gangster!

“But I learned the innermost secrets of their lives. You will be surprised to learn of the dim and remote regions of the mind into which it led me. I think I discovered the real place in nature of the hypnotic condition in the lower animals and men. I have an entirely new explanation of the so-called subconscious mind and the reason for its survival in man. I think that I can prove that Freud’s entire conception is based on a fabric of fallacy. No man can ever attain to anywhere near a true conception of the subconscious in man who does not know the primates under natural conditions.”

But the Boer farmers began drifting back to the land and their ruined farms, and farmers and baboons have always been deadly enemies — there is no raider of farm crops to equal a baboon. With the farmers came their guns, and an end to any trust the baboons had developed for Marais. His work now impossible, he moved back to Pretoria to work as an advocate and a journalist, and despite recurrent bouts of “bad health”, he continued his scientific research at every opportunity.

His work on termites led him to a series of stunning discoveries. He developed a fresh and radically different view of how a termite colony works, and indeed of what a termite colony is. This was far in advance of any contemporary work. In 1923 he began writing a series of popular articles on termites for the Afrikaans press and in 1925 he published a major article summing up his work in the Afrikaans magazine Die Huisgenoot.

Few people spoke Afrikaans then, as now, but it’s quite similar to the Dutch it stemmed from and any Dutchman or Fleming can read it without difficulty.

Maurice Maeterlinck was a leading literary figure of the time. In 1911 he won the Nobel Prize for literature following the success of his play The Bluebird. In 1901 he had written The Life of the Bee, a mixture of natural history and philosophy, but he was a dramatist and a poet, not a scientist. He was also a Fleming.

In 1926, one year after Die Huisgenoot published Marais’s article, Maeterlinck stole Marais’s work and published it under his own name, without acknowledgement, in a book titled The Life of the White Ant, first published in French and soon afterwards in English and several other languages.

Maeterlinck’s book was met with outrage in South Africa. Later, in 1935, Marais wrote to Dr Winifred de Kok in London as she was beginning her English translation of The Soul of the White Ant:

“You must understand that it was a theory which was not only new to science but which no man born of woman could have arrived at without a knowledge of all the facts on which it was based; and these Maeterlinck quite obviously did not possess. He even committed the faux pas of taking certain Latin scientific words invented by me to be current and generally accepted Latin terms.

“The publishers in South Africa started crying to high heaven and endeavoured to induce me to take legal action in Europe, a step for which I possessed neither the means nor inclination. The press in South Africa, however, quite valorously waved the cudgels in my behalf. The Johannesburg Star [South Africa’s biggest English-language daily newspaper] published plagiarized portions which left nothing to the imagination of readers. The Afrikaans publishers of the original articles communicated the facts to one of our ambassadorial representatives in Europe and suggested that Maeterlinck be approached. Whether or not this was done, I never ascertained. In any case, Maeterlinck, like other great ones on Olympus, maintained a mighty and dignified silence.”

The 1927 files at The Star to which Marais referred were checked and confirmed 40 years later by American writer Robert Ardrey, author of African Genesis. “Maeterlinck’s guilt is clear,” Ardrey wrote. It is easily confirmed by a comparison of the two books. Marais’s point is indisputable: his picture of the termitary is startlingly original, it could not possibly have been hypothesised or inferred without a great deal of original research, at the very least — and yet there it is in Maeterlinck’s book.

Though Marais made light of the issue in his letters of later years, he never regained the clear focus and command that marked his earlier scientific investigations before Maeterlinck committed his plagiarism. It was a bitter blow for Marais, the last of many.

“I find no record of scientific accomplishment after 1927,” Ardrey wrote.

Life went on for Marais, after a fashion. He wasn’t entirely embittered, still retaining his famed charm, especially with children, which tells much — he spent much of his time with children, wreathing them in magic with his wonderful tales.

Robert Ardrey tells the story:

“A good many years ago Professor J. S. Weiner, Oxford’s celebrated anatomist, told me a story about Marais that better than any other I have ever heard probed the hidden darkness. Weiner is a South African who grew up in a district of Pretoria called Sunnyside and many years later achieved world fame when with Kenneth P. Oakley of the British Museum, he proved that the Piltdown skull, then presumed to be the remains of man’s earliest ancestor, was a hoax. I had never met Weiner when, in Rome for a conference, he came to our apartment to spend an evening. And he startled me, for he had no more than found a chair before he asked why I had dedicated African Genesis to Marais.

“There was little to explain. I said that I felt science had neglected Marais, and that, while I was not a scientist, it had seemed the least I could do. ‘I’m glad you did it,’ said Weiner. ‘I know I’ve always felt guilty about him.’ And he told his story.

“When Weiner was a boy in Sunnyside one of the most thrilling of events was the sight of Eugène Marais — dignified, dressed always in immaculate white — walking down towards the river in the evening. It was a signal to all the children along the street. They came piling out of yards and gardens and upstairs rooms to follow Marais to the river. There he’d find an old stump or a log to sit on, while they arranged themselves on the ground. And he would tell stories. All acquaintances recall him as one of the most consummate story-tellers of his time and place, but the mightiest of witnesses were the children at his feet, listening with long-held breath to his stories of bush and veld and dusty roads where mambas slink. The dark would come on. He would rise and go home, and the children, full of magic, would return to new worlds.

“Marais had a room in a house just a few doors down the street. Weiner’s sister, friendly with several girls who lived in the house, had come to know him, and one day asked Weiner to return a book to Marais’s room. Clutching the book, consumed by the excited possibility of meeting the magic-maker alone, he went to the house, found the room, knocked. There was no answer. He tried the door. It was unlocked. He entered cautiously. The room was dank with disorder. And there was a strange smell. He put down the book and fled.

“Many years later — in 1940, years after Marais was dead — Weiner was a medical student at St George’s Hospital in London. In a pharmacological course the students were learning to identify a variety of pharmaceutical items. He was handed a sample of some drug with a very queer smell. Instantly he had a vivid recollection — a total recall — of a room somewhere. He struggled to identify the room, and knew it somewhere in South Africa. Then it came to him — Marais’s little room. The drug was morphine.”

— Robert Ardrey, 1969, Introduction, The Soul of the Ape

Between continuing bouts of “ailing health”, whether due to morphine or malaria, Marais worked as an advocate, he wrote articles and stories. But what should have been written and bequeathed to the world wasn’t done. The Soul of the White Ant was published in Afrikaans, and then later in English, but the more scientific work from his notes and studies that should have amplified it was not forthcoming.

The planned companion volume on the psyche of the baboon, The Soul of the Ape, was never finished. Several excerpts were published in Afrikaans, but the book itself didn’t appear.

A further work summing up and integrating his findings and conclusions in the two branches of his investigations should have followed, but it didn’t.

In 1936, Eugène Marais killed himself with a shotgun on a farm near Pretoria.